Publications

Investment Planning via Switzerland

Simon Gabriel;

in: ASA Bull. 1 / 2013, p. 11 et seqq.

I. The Problem

A. Potential Sunset of Existing EU BITs

Global foreign direct investment (“FDI”) remains significant and is expected to further grow in the next few years, irrespective of the delicate situation in the financial markets:

“Global foreign direct investment (FDI) flows exceeded the pre-crisis average in 2011, reaching $1.5 trillion despite turmoil in the global economy. […]

Longer-term projections show a moderate but steady rise, with global FDI reaching $1.8 trillion in 2013 and $1.9 trillion in 2014, barring any macroeconomic shocks.”1

A firm prerequisite for the continuing success of FDI is a solid basis of legal certainty for foreign investors:

“Prerequisite for the functioning and further development of international investment activity is greatest possible legal certainty.”2

In recent years, however, there has been a lot of discussion on the relationship between the laws of the European Union (“EU”) and Bilateral Investment Treaties (“BITs”) of its member states.3 Considering the most recent developments it appears that (i) the future of intra-EU BITs4 is in jeopardy5 and (ii) extra-EU BITs of EU-member states are in flux.6 In particular, the European Commission has urged member states to terminate their intra-EU BITs. This affects legal certainty of intra-EU BIT-protection already in the near future.7

Considering foreign investors’ general wish for long-term legal certainty a growing interest for planning foreign investments via stable countries outside EU may be expected. In particular, abolishment of intra-EU BITs and modification of extra-EU BITs is likely to trigger investment structures via third countries like Switzerland which still have a solid network of BITs with relevant EU- and third countries in place.

Against this background the present contribution analyses which minimal nationality requirements an investor must fulfil in order to structure foreign investment via Switzerland.

B. Scope of the Present Analysis

In order to achieve stable Swiss BIT-protection a group of companies that is not or not exclusively domiciled in Switzerland may want to structure a foreign investment into a third country via Switzerland.

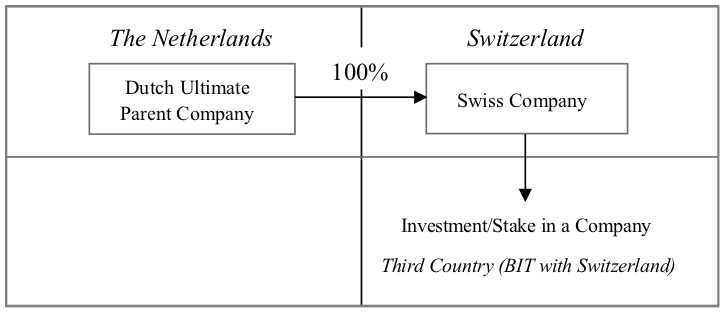

First Example:

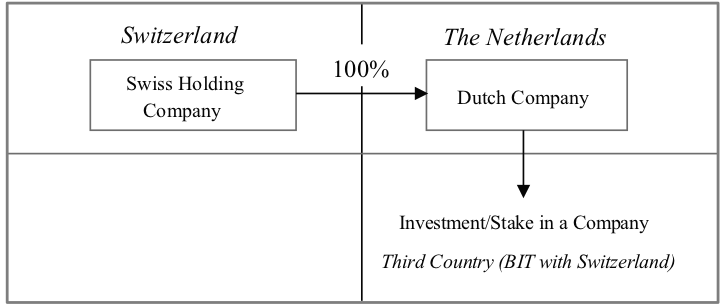

Second Example:

In such or similar constellations the question arises under which requirements the Swiss company is qualified as Swiss investor under an applicable BIT between Switzerland and a target country.

The question whether the Swiss subsidiary in the first example may, in turn, also act as holding company for a further subsidiary in the target country is also an issue in this context.8

In the second example a Swiss holding company is established as ultimate parent company of a corporate structure in order to obtain Swiss BIT-protection.9

The present contribution analyses (i) recent practice of arbitral tribunals on nationality planning and (ii) particular requirements which must typically be fulfilled for nationality planning via Switzerland.10 In conclusion a short “investment planning test” is derived from the findings of the present analysis.

II. General Remarks regarding Nationality Planning

A. Legitimacy of Nationality Planning

It is fair to ask whether and to what extent nationality planning, which is sometimes also referred to as “nationality shopping”, is legitimate in the context of FDI. In addition to an analysis of legal doctrine it is vital to embrace the position of the bodies that typically decide on the nationality criterion agreed upon in BITs, i.e. arbitral tribunals.11

Leading commentators opine that there is no reason why a prudent investor should not organize its investment in a way that affords maximum protection under existing treaties.12 This liberal approach has also been adopted in several investment arbitration awards that are publicly available:

In the case Aguas del Tunari v. Bolivia13, the arbitral tribunal held: “The language of the definition of national in many BITs evidences that such national routing of investment is entirely in keeping with the purpose of the instruments and the motivations of the State Parties.”14 This observation is vital for the accurate comprehension of BITs. The states which conclude BITs aim at creating an attractive environment for investors and investments. Developing states which are typically seeking foreign investment do not only accept, but rather aim to achieve that as many investors as possible may choose the route via a certain BIT in order to enhance capital inflow. The same is true for developed states which also profit if investors structure via corporations in their country by collecting taxes and offering financial, legal and other services. Hence, the opportunity of nationality planning appears to be part of the proper purpose of BITs in general.

In the case Soufraki v. United Arab Emirates15, the arbitral tribunal found that Mr Soufraki, who failed to establish his Italian nationality, could have avoided this result by structuring his investment via an Italian corporation.16 This is a further clear statement in favor of proper nationality planning.

In the case Saluka v. Czech Republic, the arbitral tribunal did not rely upon the fact that Claimant, a Dutch corporation, was merely a shell company controlled by Japanese owners as the Czech-Dutch BIT exclusively referred to the state of incorporation for determination of nationality.17 The Dutch shell company was thus qualified to obtain protection under the Czech-Dutch BIT.

These examples demonstrate that arbitral tribunals have, with good reason, relied upon the definitions of nationality as provided for in the applicable BITs. There are no indications that intentional nationality planning would or should be disapproved. Rather, it appears that the principle of pacta sunt servanda is strictly applied by arbitral tribunals. This conclusion is confirmed by comments of leading scholars:18

“An analysis of practice indicates that tribunals have given effect to the definitions of corporate nationality contained in BITs. If the requirements for corporate nationality under the respective BIT were met, the tribunals typically refused to second guess it.”19

B. Limits of Nationality Planning

Against the background of the above findings in favour of nationality planning the question arises which limits must nevertheless be considered:

Retroactive planning: While prospective nationality planning is generally accepted, legal doctrine maintains that retroactive measures to obtain advantages from BITs are not admissible.20 This position has also been taken by arbitral tribunals applying different legal concepts:

Phoenix v. Czech Republik:21 After the facts leading to a dispute had already occurred, a Czech investor sold an investment to the Israeli company “Phoenix”. Phoenix, thereupon, brought action under a Czech-Israeli BIT. The said measure which was only taken after the dispute had started, led the tribunal to the statement that Phoenix could only rely on facts which occurred after Phoenix made an investment: “The Tribunal is limited ratione temporis to judging only those acts and omissions occurring after the date of the investor’s purported investment.”22

Banro American Resources v. Democratic Republic of Congo23 A Canadian company intended to initiate ICSID arbitration based upon an investment agreement with the Democratic Republic of Congo containing a respective arbitration agreement. However, when a dispute arose and the Canadian company noticed that only the United States, but not Canada, were part of the ICSID Convention it assigned its claim to an U.S. affiliate who, thereupon, acted as Claimant in ICSID arbitration. The publicly available excerpts of the award show that the arbitral tribunal disapproved of this last-second assignment and thereby relied on the legal concept nemo plus iuris transferre potest quam ipse habet: “Having never existed for the benefit of Banro Resource, the right of access to ICSID cannot be viewed as having been ‘extended’ or ‘transferred’ to its affiliate, Banro American”.24

Hence, it may be concluded that retroactive nationality planning (i.e. measures taken after the facts leading to a dispute have already taken place) bears a considerable risk of not being accepted by arbitral tribunals.

Piercing of the corporate veil in cases of fraud or malfeasance: Pursuant to various investment cases and relevant legal doctrine, piercing of the corporate veil is limited to cases of fraud or malfeasance which must involve a misuse of corporate personality.25 At the same time it is expressly maintained that structuring investments through establishment of corporations in different jurisdictions does not as such constitute a wrongdoing and is thus not a basis for piercing of the corporate veil.26

C. First Conclusion

In conclusion the following applies:

Prospective nationality planning is generally accepted by arbitral tribunals, if all requirements of the applicable BIT are met.

Retroactive measures (taken after the facts leading to a dispute have occurred) to obtain BIT-protection and misuse of corporate personality in cases of fraud or malfeasance form limits for free nationality planning.

Consequently, if the nationality requirements of Swiss BITs with third countries are met and in absence of the narrow limits as mentioned herein above, investment planning via Switzerland is available for foreign investors.

Against this background, the nationality requirements of Swiss BITs are analyzed and applied to the initially described group structures.27

III. Requirements for Investment Planning Via Swiss BITs

A. Swiss Network of BITs

The Swiss BIT network is officially published by the State Secretariat for Economic Affairs (“SECO”).28 Switzerland concluded BITs with the following EU member states and EU candidate states:

- Bulgaria;

- Czech Republic;

- Estonia;

- Hungary;

- Latvia;

- Lithuania;

- Macedonia;

- Poland;

- Romania;

- Serbia;

- Slovakia;

- Slovenia.29

Furthermore, Switzerland maintains BITs with over 110 countries worldwide, including China, India and Russia.30 It goes without saying that no general statements, that are valid for all Swiss BITs, can be made in the following.

Publications on Swiss BITs in some instances refer to a so-called “Swiss Model BIT”. Fact is, however, that the Swiss state continuously amends its standard BIT-clauses and does not officially publish them for the time being. Consequently, there is no other alternative than to appreciate the nationality requirements of each single BIT individually.

At the same time, an analysis of recent Swiss BITs with EU member states and EU candidate countries as well as a publication by Mr MICHAEL SCHMID31 on Swiss BITs leads to typical requirements which are relevant for the present subject:

On the one hand a Swiss investor must be organized or incorporated under the laws of Switzerland.32

On the other hand and particularly in more recent Swiss BITs a “real economic activity”33 in Switzerland is required by the Swiss investor.34

The same criteria apply in cases where a legal entity organized under the laws of a third country is controlled by a Swiss entity.35 In such situations the controlling Swiss entity must typically also be organized under the laws of Switzerland and demonstrate a “real economic activity” in Switzerland.36

So-called “denial of benefits clauses”37 for entities organized under the laws of Switzerland and with a “real economic activity” in Switzerland which are, however, controlled by entities or individuals in third countries may exist in specific BITs. However, as stated in the ICSID case Tokio Tokeles v. Ukraine38 it is not for an arbitral tribunal to read such a clause into the text of a BIT, if it is not expressly provided for.39

This said the following sections will deal with the typical nationality requirements pursuant to most Swiss BITs from a Swiss legal perspective.40

B. The Requirement of an Entity Incorporated under Swiss Laws

The nationality requirement of incorporation under the laws of a particular country is commonplace in the international practice on BITs.41 The importance of the incorporation requirement has been confirmed in the Official Considerations of the Swiss Federal Council (“Botschaft des Bundesrats”) regarding BITs concluded with Serbia and Montenegro42. Same as most of the BITs in question, the BIT with Serbia and Montenegro relies on the laws of the state of incorporation and real economic activity in that state.43 In the Official Considerations of the Swiss Federal Council it is stated:

“In case of legal entities the qualification as investors is either derived from the laws of the state where the entity has been incorporated (criteria of incorporation) and where it has its seat or from relevant control (criteria of control44, …)”.45

The requirement of “real economic activity” in Switzerland is not mentioned in the Official Considerations of the Swiss Federal Council even though it is reflected in the language of the relevant BITs.46 It follows that at least in the understanding of the Swiss drafters the requirement of incorporation was meant to be key for determination of the nationality of the investor.47

C. The Requirement of “Real Economic Activity”

Considering the fact that the Official Considerations of the Federal Council do not mention the second requirement, i.e. “real economic activity” in the state of the investor, the question arises which weight the said criterion should entail.

Mr MICHAEL SCHMID in his publication on Swiss BITS expressed the following opinion:

“For legal entities to qualify as nationals, their incorporation or organisation under the laws of a contracting party is sufficient. In more recent BITs concluded by Switzerland, the requirement of a real economic activity in Switzerland was added (in order) to exclude mailbox companies from BIT coverage.”48

It thus appears that the incorporation requirement is valid and decisive as long as a Swiss entity can demonstrate activity in Switzerland which goes beyond mere maintenance of a mailbox. This understanding is confirmed by the available concepts of interpretations for legal terms in international treaties:49

Ordinary meaning to be given to terms:50 The Swiss Federal Tribunal found in a case regarding international tax issues that in absence of “administration, direction of current transactions and company management” in a certain country, there was no real economic activity of a company in the said country.51 It may be concluded e contrario that in cases of effective “administration, direction of current transactions and company management” in Switzerland, real economic activity in Switzerland exists.52 The said conclusion is also reasonable without relying on the authority of the Swiss Federal Tribunal: “Administration, direction of current transactions and company management” comprises actions and thus activity as well as economic focus by actually dealing with business transactions.

A company established in Switzerland acts through its directors, employees and/or representatives. It follows that at least one director, employee or representative must perform the defined economic activity in Switzerland by e.g. managing the foreign investment through the Swiss company in Switzerland. Neither the language in question nor the definition of the Federal Tribunal excludes that the economic focus of the activity is limited to the handling of the foreign investment. Consequently, a Swiss subsidiary in charge of a foreign investment which is managed and administered by a director, employee or representative in Switzerland meets the legal requirement of “real economic activity” in Switzerland.53Object and purpose of the treaty:54 As already mentioned above, the main purpose of the drafters of the relevant BITs was to exclude mailbox-companies.55 Furthermore, the fact that the Official Considerations of the Swiss Federal Council regarding BITs concluded with Serbia and Montenegro do not even mention the requirement of “real economic activity” in Switzerland leads to the understanding that this requirement was not discussed beyond its grammatical meaning.

With regard to the purpose at issue, it is the general concept behind any BIT to create an attractive environment for investors. The general findings in the already mentioned case Aguas del Tunari v. Bolivia do also apply to BITs between Switzerland and third countries: It is typically the very idea of both state-parties to a BIT to attract investors via such BIT.56 The routing of an investment via such BIT is thus in the very interest of both parties to a BIT. There are no indications that Switzerland intended to restrict investment planning beyond the mentioned exclusion of mailbox companies. Hence, the concept derived in the grammatical interpretation is also in line with interpretation pursuant to the purpose of BITs.57

Based on the above interpretation of “real economic activity” in Switzerland it is sufficient for a foreign investor to establish a Swiss subsidiary with offices and directors, a few employees or representatives who manage the company and the foreign investment in Switzerland. In the author’s view also situations of one single director, employee or representative of the Swiss company who manages the Swiss company and the foreign investment in Switzerland are qualified to satisfy the requirement of “real economic activity” in Switzerland.

Finally, the delicate question arises whether a Swiss company which (i) is domiciled in the offices of a Swiss representative (without any own personnel) and (ii) exclusively acts through its Swiss representative should be considered to perform any “real economic activity” in Switzerland. In the author’s view the answer to this question depends upon the actual position of the Swiss representative: (i) If the Swiss representative indeed handles “administration, direction of current transactions and company management” in Switzerland, his activities should be fully attributable to the company. Consequently, the “real economic activity”-requirement would be met.58 (ii) If the Swiss representative is, however, confined to forwarding correspondence to the foreign parent company, where the actual administration takes place, there is a significant risk that the mailbox- exclusion would be applied by an arbitral tribunal.

D. Limits of Investment Planning via Switzerland

The general limits of nationality planning also apply for investment planning via Switzerland: (i) Limits expressly provided for in a specific BIT (e.g. “denial of benefits clauses”); (ii) retrospective nationality planning and (iii) fraud or malfeasance which involves a misuse of corporate personality.59

Further limits to investment planning via Switzerland are not apparent.

E. The Swiss Subsidiary as Holding Company of Another Subsidiary in the Target Country

With respect to the first example of a corporate structure as provided for herein above60, the question arises whether Swiss BIT-protection would generally be available, if the Swiss subsidiary invested via a further subsidiary in the said target country. In such a constellation the Swiss company would have a double function: On the one hand it would be a subsidiary of the Dutch ultimate parent company.61 On the other hand and at the same time, it would fulfill the function of a holding company with respect to another subsidiary in the target country.62 It is thereby assumed that the general requirements of incorporation and real economic activity would be met with respect to the Swiss company.

The question may be divided in two sub-questions: (i) Is control of a subsidiary in the target country sufficient to be qualified as an investor? (ii) If yes, does the fact that the (Swiss) investor is again controlled by another ultimate parent company (in our first example by the holding company in the Netherlands) negatively affect its qualification as investor? Both questions must be answered in application of the individual BITs at issue.63

First sub-question: The following statement of Mr MICHAEL SCHMID is instructive in this respect:

“The Swiss BITs traditionally cover investments that are controlled by Swiss nationals or legal entities. ‘Control’ under international investment law is a very broad concept and can include also minority shareholders or management responsibility. In addition, since the entity can be controlled ‘directly or indirectly’, investments also held through host state entities or third state entities are covered by the BIT. The recognition of (indirect) shareholding as a form of investment has made the issue of nationality of a legal entity lose some of its edge.”64

Consequently, for most Swiss BITs the first question is to be answered in the affirmative.

Second sub-question: If not provided otherwise in a specific BIT, the fact that a (Swiss) investor, which controls an entity in the target country is, in turn, again controlled by e.g. a Dutch parent company, does not change the legal situation. This understanding has been expressly confirmed by the already mentioned investment cases Soufraki v. United Arab Emirates and Saluka v. Czech Republic.65 In particular, in the latter case the arbitral tribunal expressly accepted a constellation in which a “shell company” in the Netherlands has been established by Japanese parents exclusively to obtain protection of a Dutch-Czech BIT.

Hence, if the Swiss company makes an investment via another company in the target country, Swiss BIT-protection is usually available. Only where such structures are expressly excluded by a “denial of benefits clause” in a specific BIT, BIT-protection may be denied.66

F. Swiss Holding as Ultimate Parent Company

Finally, the question arises whether or not Swiss BIT-protection would, as a rule, be available for structures in which a Swiss holding company controls e.g. a Dutch subsidiary which, in turn, makes an investment in a target country.67 It is again assumed that the general requirements of incorporation and real economic activity would be met by the Swiss holding company.

While the answer to the question may again differ depending on the BIT at issue, it appears that indirect control of an investment via a third- country company does, generally speaking, not exclude Swiss BIT-protection:

“In addition, since the entity can be controlled ‘directly or indirectly’, investments also held through host state entities or third state entities are covered by the BIT.”68

Moreover, such constellations are expressly accepted in various Swiss BITs. As an example the Swiss BIT with Bulgaria may be quoted:

“For purposes of this treaty, the term ‘investor’ refers regarding both treaty parties to legal entities which are incorporated pursuant to the laws of a third state or of the other treaty party and controlled directly or indirectly by citizens of the relevant treaty party or legal entities, which have their seat in the territory of the relevant treaty party and there develop a real economic activity.”69

It may be noted that the requirement of “real economic activity” is again expressly provided for with respect to the (Swiss) holding company.

Consequently, in absence of any language to the contrary in the applicable BIT, the Swiss holding company is entitled to BIT-protection.

At the same time it should not be omitted that the corporate structure must be in place at the moment when the facts leading to the dispute take place. Otherwise, there is a considerable risk that a tribunal would not accept BIT-protection due to inadmissible retroactive nationality planning.70

G. Second Conclusion

A foreign company that structures an investment in a third country via a company in Switzerland is in a position to rely on a Swiss BIT with that third country, if

the Swiss legal entity is incorporated pursuant to the laws of Switzerland and thus has its seat in Switzerland,

at least the company administration and management of the foreign investment (or any other operations) are effected by directors, employees or representatives in Switzerland, and

none of the general limits of nationality planning apply.

IV. Final Conclusion: “Swiss Investment Planning Test”

An investor who intends investment planning via Switzerland should

consider each item of the following test:71

A Swiss legal entity is incorporated pursuant to the laws of Switzerland.

The Swiss entity makes a foreign investment into a target country which maintains a BIT with Switzerland (including investments via companies in the target country or companies in third countries).

The Swiss entity actually handles administration, direction of current transactions and company management at least with respect to the foreign investment through directors, employees or representatives in Switzerland.

The Swiss entity is set up as a measure of prospective nationality planning (and not as retroactive measure after e.g. a dispute has already arisen).

No specific agreements in the applicable BIT exclude structuring via a Swiss entity (e.g. “denial of benefits clause”).

No situation of misuse of the Swiss entity’s corporate personality applies.

-

See World Investment Report 2012, UNCTAD, United Nations Publication 2012, p. xi. ↩︎

-

See BÖCKSTIEGEL, Aktuelle Probleme der Investitions-Schiedsgerichtsbarkeit aus der Sicht eines Schiedsrichters, SchiedsVZ 3/2012, p. 113 (informal translation from German original). ↩︎

-

For an overview see TIETJE, Bilaterale Investitionsschutzverträge zwischen EU-Mitgliedstaaten (Intra- EU-BITs) als Herausforderung im Mehrebenensystem des Rechts, Beiträge zum Transnationalen Wirtschaftsrecht, Heft 104, 2011. ↩︎

-

For a definition see TIETJE, FN 3, p. 5. ↩︎

-

See STRIK, Investment Protection of Sovereign Debt and Its Implications on the Future of Investment Law in the EU, (2012) 29 J. Int. Arb 2, p. 195 and 197. ↩︎

-

See CHAISSE, Promises and Pitfalls of the European Union Policy on Foreign Investment – How Will the New EU Competence on FDI Affect the Emerging Global Régime?, Journal of International Economic Law (2012), p. 2 et seq.; Press Release of the European Commission Directorate-General for Trade dated 21 June 2012 available at: http://europa.eu/rapid/pressReleasesAction. do?reference=IP/12/677& (visited on 7 September 2012): “When concluded, the EU level agreements including investment protection will replace the Member States’ Bilateral investment Treaties with the same third countries.” ↩︎

-

See STRIK, FN 5, p. 195 and 198; Award dated 26 October 2010, PCA Case No. 2008 – 13, Eureko B.V. v. The Slovak Republic, sec. 181, where the EU Commission in its observations concluded that the pacta sunt servanda rule only applies to extra-EU Bits, available at: http://italaw.com/documents/EurekovSlovakRepublicAwardonJurisdiction.pdf (visited on 7 September 2012) ↩︎

-

See herein below, sec. III.E for specific comments in this respect. ↩︎

-

See herein below, sec. III.F for specific comments in this respect. ↩︎

-

The issue of the nationality of individuals is not addressed in the present contribution. ↩︎

-

See REINISCH, Prospects of Investment Arbitration, in: Hoffmann (ed.), ASA Special Series No. 34, 2010, p. 251; TIETJE, FN 3, p. 7. ↩︎

-

See SCHREUER, Nationality of Investors: Legitimate Restrictions vs. Business Interests, 24 ICSID Review (2009), p. 524. ↩︎

-

ICSID Case No. ARB/02/3, available at: http://icsid.worldbank.org/ICSID/FrontServlet?requestType= CasesRH&actionVal=showDoc&docId=DD629_En&caseId=C210 (visited on 23 July 2012). ↩︎

-

ICSID Case No. ARB/02/3, sec. 332. ↩︎

-

ICSID Case No. ARB/02/7. ↩︎

-

See SCHREUER, FN 12, p. 524. ↩︎

-

See SCHREUER, FN 12, p. 525. ↩︎

-

See HUNTER in: Tietje et al. (ed.), The Determination of the Nationality of Investors under Investment Protection Treaties, Beiträge zum Transnationalen Wirtschaftsrecht, Heft 106, 2011, p. 51; SCHILL, Investement Treaties: Instruments of Bilateralism or Elements of an Evolving Multilateral System?, Paper for the 4th Global Administrative Law Seminar, Viterbo 2008, p. 13: “Above all, arbitral tribunals have so far declined to take a look behind the corporate veil in order to determine the nationality of corporate investors …”. ↩︎

-

See SCHREUER, FN 12, p. 525. ↩︎

-

See SCHREUER, FN 12, p. 526. ↩︎

-

ICSID Case No. ARB/06/5 available at: http://icsid.worldbank.org/ICSID/FrontServlet?requestType= CasesRH&actionVal=showDoc&docId=DC1033_En&caseId=C74 (visited on 24 July 2012). ↩︎

-

ICSID Case No. ARB/06/5, sec. 68. ↩︎

-

ICSID Case No. ARB/98/7, excerpts available at: http://icsid.worldbank.org/ICSID/FrontServlet?requestType=CasesRH&actionVal=showDoc&docId=DC577_En&caseId=C173 (visited on 24 July 2012). ↩︎

-

ICSID Case No. ARB/98/7, sec. 5 of the published parts. Furthermore, the tribunal apparently found that Banro group attempted to take advantage of diplomatic protection and ICSID arbitration which excluded each other (sec. 24 of the published parts). ↩︎

-

See SCHREUER, FN 12, p. 526 with reference to various cases of investment tribunals and a case of the International Court of Justice (Barcelona Traction). ↩︎

-

See SCHREUER, FN 12, p. 526. ↩︎

-

See herein above, sec. I.B for diagrams of the mentioned structures. ↩︎

-

See official list including links to the individual BITs in the official Systematic Collection of Swiss Law (version July 2012; “Swiss BIT List”) available at: http://www.seco.admin.ch/ themen/00513/00594/04450/index.html?lang=en (visited on 21 September 2012). ↩︎

-

See Swiss BIT List, FN 28. ↩︎

-

See Swiss BIT List, FN 28. ↩︎

-

Deputy Head of the “International Investments and Multinational Enterprises” Unit at the State Secretariat for Economic Affairs (“SECO”) in the Swiss Federal Department of Economic Affairs. ↩︎

-

See SCHMID, Swiss Investment Protection Agreements: Most-Favoured-Nation Treatments and Umbrella Clauses, Zurich 2007, p. 16. ↩︎

-

Sometimes also referred to as “effective economic activites”, see PERKAMS in: Tietje et al. (ed.), The Determination of the Nationality of Investors under Investment Protection Treaties, Beiträge zum Transnationalen Wirtschaftsrecht, Heft 106, 2011, p. 15. ↩︎

-

See ROMANETTI, Defining Investors: Who is Eligible To Claim?, (2012) 29 J. Int. Arb. 3, p. 236 for general remarks in this respect; SCHMID, FN 32, p.16. ↩︎

-

See also herein below, sec. III.D. for specific comments in this respect. ↩︎

-

See e.g. Swiss BIT with Bulgaria (Systematic Collection of Swiss Law, no. SR 0.975.221.4), Art. 1.c; Swiss BIT with Latvia (Systematic Collection of Swiss Law, no. SR 0.975.248.7) , Art. 1.c; Swiss BIT with Romania (Systematic Collection of Swiss Law, no. SR 0.975.266.3), Art. 1.c; and many others. ↩︎

-

See HAPP in: Tietje et al. (ed.), The Determination of the Nationality of Investors under Investment Protection Treaties, Beiträge zum Transnationalen Wirtschaftsrecht, Heft 106, 2011, p. 61 et seqq. for a general analysis regarding denial of benefit clauses. ↩︎

-

ICSID Case No. ARB 02/18, Award on Jurisdiction, availabe at: http://icsid.worldbank.org/ ICSID/FrontServlet?requestType=CasesRH&actionVal=showDoc&docId=DC639_En&caseId=C220 (visited on 25 July 2012). ↩︎

-

ICSID Case No. ARB 02/18, Award on Jurisdiction, sec. 36: “In our view, it is not for tribunals to impose limits on the scope of BITs not found in the text, much less limits nowhere evident from the negotiating history”. ↩︎

-

It can, however, not be excluded that a partner-state of Switzerland in a particular BIT may be of a different view. ↩︎

-

See ROMANETTI, FN 34, p. 234; SCHREUER, FN 12, p. 522, where it is referred to as “the most commonly used criteria”. ↩︎

-

See Official Considerations of the Swiss Federal Council regarding BITs with Serbia and Montenegro, Guyana, Aserbaidschan, Saudi-Arabia and Colombia, dated 22 September 2006, BBl 2006, 8455 et seqq. ↩︎

-

See Swiss BIT with Serbia and Montenegro (Systematic Collection of Swiss Law, no. SR 0.975.268.2), Art. 1 para. 2.a. ↩︎

-

Only where applicable based on the language of the respective BIT (e.g. Guyana and Columbia). ↩︎

-

Considerations of the Federal Council, FN 42, p. 8467 (informal translation). ↩︎

-

See Swiss BIT with Serbia and Montenegro, FN 43, Art. 1 para. 2.a. ↩︎

-

See also PERKAMS, FN 33, p. 14, where the term is not defined, either. ↩︎

-

See SCHMID, FN 32, p.16, emphasis added. ↩︎

-

See art. 31 and 32 of the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties. ↩︎

-

See art. 31 para. 1 Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties. ↩︎

-

See BGer 2A.239/2005, sec. 3.6.4. (informal translation). ↩︎

-

This applies at least from a Swiss legal perspective and there are no indications that different standards should be applied. ↩︎

-

This understanding is also in line with the so-called “effective link” principle, pursuant to which nationality must correspond with a factual situation in the sense of a genuine and effective connection; see HUNTER, FN 18, p. 44 with reference to the so-called Nottebohm Case. ↩︎

-

See art. 31 para. 1 Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties. ↩︎

-

SCHMID, FN 32, p.16. ↩︎

-

See herein above, sec. II.A. ↩︎

-

BITs are treaties negotiated and concluded between states. The result is thus not a judicial act of legislature by an existing legal system, but rather a negotiated contract between states at eye-level. No state-party may require that the treaty is interpreted in accordance with its legal system, which is, as a rule, different from the legal system of the other state. Consequently, treaties cannot be interpreted in the greater legal system of a country and a systematical interpretation is thus obsolete. This understanding is in line with art. 27 of the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties. ↩︎

-

See also HUNTER, FN 18, p. 51, pursuant to which the imposition of a rigorous requirement that a corporate investor be required to have an effective or genuine link to the home state is problematic and should be rejected. ↩︎

-

See herein above, sec. II.B. ↩︎

-

See herein above, sec. I.B, first diagram. ↩︎

-

See first example herein above, sec. I.B. ↩︎

-

See also LEW in: Horn/Kröll (eds.), Arbitrating Foreign Investment Disputes, Kluwer 2004, p. 268 et seqq. for an analysis of shareholding via multi-tier arrangements and issues of “portfolio investment”. ↩︎

-

See herein above, sec. III.A. ↩︎

-

SCHMID, FN 32, p.16 et seq. ↩︎

-

See herein above, sec. II.A. (ii) and (iii). ↩︎

-

See also herein above, sec. III.A. ↩︎

-

See herein above, sec. I.B, second diagram. ↩︎

-

SCHMID, FN 32, p.16 et seq., emphasis added. ↩︎

-

Swiss BIT with Bulgaria (SR 0.975.221.4), Art. 1 Para. 3 Sec. c (informal translation). ↩︎

-

See herein above, sec. III.D. ↩︎

-

This test does exclusively cover the issue of nationality of a Swiss corporate investor. ↩︎